The FPJQ at 50

As the Fédération professionnelle des journalistes du Québec (FPJQ) celebrates its 50th anniversary, André Lavoie reviews the organization’s history and some of the challenges it has faced over the years.

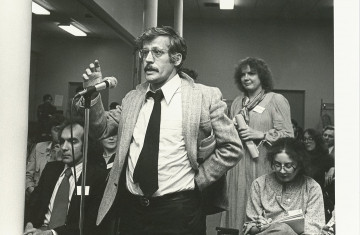

Former journalist and editorial director of Radio-Canada Louis Martin at a general assembly of the FPJQ in the 1980s. – photo: Claire Beaugrand-Champagne

In 1971, the Fédération professionnelle des journalistes du Québec/Quebec Federation of Journalists (FPJQ) held a conference under the theme L’information, ça sert à fourrer le monde (Information is a way to screw people). One of the workshops addressed a topic that was current at the time: Are journalists all PQ supporters?

The language used to attract professionals to the FPJQ’s annual networking, discussion and training event has certainly changed since then, but the Fédération has tried to remain in step with a profession that ironically doesn’t always get good press.

Since its launch in 1969, two primary concerns have dictated the organization’s actions: freedom of the press and the public’s right to information. These two ambitious goals have been somewhat overshadowed by hot topics in the history of the FPJQ: the improvement of working conditions for professionals in the field; the challenging and laborious establishment in 1973 of the Conseil de presse, the organization that handles media complaints; and the transformation of the FPJQ from a body of unions and associations into a group of individuals in 1992.

Two primary concerns have dictated the actions of the FPJQ: freedom of the press and the public’s right to information.

During the first decade of the FPJQ, the union movement was in its glory days, as were the press associations. But who remembers the Association des journalistes anglophones, the Association des pigistes en information or the Association des journalistes de plein air? Still, some associations have carried on along with the FPJQ, such as the Association des journalistes indépendants du Québec, which was created in 1988 by freelancers who joined forces to fight for better working conditions. These efforts have received support from the Fédération nationale des communications.

The beginnings of any organization are usually filled with great enthusiasm, but over time, reality sets in, sometimes brutally. For many years, the FPJQ relied on a handful of devoted collaborators, all of whom were volunteers. This inevitably curbed the organization’s ambitions.

The FPJQ initially set up its offices in Québec City, which seemed like a logical choice since it was close to the government, and sought to obtain substantial support for the information industry. But the move to Montreal in 1973 did not signify the start of a period of comfort and stability. In fact, the FPJQ went through a time when it operated illegally from a triplex on Panet Street, as mentioned by Claude Robillard, the executive director of the FPJQ from 1989 to 2014, in his farewell message in Le Trente. The organization went on to occupy other premises that were unsafe and inhospitable; one of its locations on Mont-Royal Avenue, where many training courses were given, was visited by burglars on three occasions.

Obviously, the thieves had no idea what kind of place they were robbing. Although the FPJQ now has three permanent employees and hires contractors for projects and events, it has experienced a great deal of financial difficulty. It was threatened with closure in the 1970s and 1980s, even though it welcomed many members during that period (nearly 250 in one year). Deficits forced the organization to refocus its mission, offer a wider range of member services and relaunch certain awards, including the coveted Judith Jasmin Award. All of this took place in a context of rapid technological transformation, which led to, among other things, the FPJQ’s first website in 1999.

The FPJQ has been heavily involved in debates regarding journalism issues, but also in debates on government transparency.

It took the FPJQ three conferences and many discussions to finally publish the Guide de déontologie, an ethics guide not only for the Fédération’s members, but for all journalists in Quebec. This was in 1996, and in spite of all the minor revolutions that have shaken the profession since—from the internet and cellphones to social media and citizen journalism—it remains a relevant reference. The* Guide de déontologie* serves as a reminder of the foundations of a trade that was brilliantly summarized by Lise Millette, the FPJQ’s former president: “To deliver information, including information people don’t want to give us.”

If the FPJQ is well known in the halls of power in Quebec and Ottawa, it isn’t only because of the notoriety of several of its leaders, including Anne-Marie Dussault, Pierre Craig, Michel C. Auger and Alain Gravel. The Fédération has always been involved in debates regarding journalism issues, as well as debates on the transparency of the government in its interactions with citizens, another recurring theme.

In the late 1960s, the consolidation and Americanization of the press were already feared. The FPJQ didn’t wait for permission to make its voice heard, both in the public sphere and in the many parliamentary committees covering the media world.

Pressures exerted by the FPJQ led to legislation governing the financing of political parties and the protection of personal information under the government of former journalist René Lévesque.

The strong positions it adopted covered many aspects of our democratic life, including the provincial government’s tendency to cover up its decision-making processes, a habit adopted by many municipal administrations over several decades. Then Quebec premier René Lévesque, a former journalist, was associated with an act governing the financing of political parties, as well as one addressing the access to documents held by public bodies and the protection of personal information in 1982.

That legislation was a major step towards countering the culture of secrecy, an aberration in any society that claims to be democratic. Unfortunately, it was also subject to attacks from detractors, some of whom had been elected. This is just one of the dark issues at the heart of the FPJQ’s battles; others include journalists being arrested for refusing to reveal their sources; fratricidal wars raging between press enterprises; the dismantling of press rooms in radio and television stations, some of which served as models and training grounds for generations of journalists; and so on.

- Why we should support Quebec’s media

- Remembering André Bureau (1935-2019)

- A journalism lab for the digital era!

Numbers may not reveal the whole story, but some are telling. In 1974, the FPJQ had 460 members; in 2015, that number was more than 2,000. This year, with 1,800 reporters, researchers, columnists, photographers and senior executives from over 250 print and electronic media outlets, the organization is still going strong. The slight decrease is by no means a disavowal of the actions or philosophy of the Fédération, though it has experienced its share of infighting.

The media crisis is not just a buzzword, a creation of the mind or the latest craze of a profession whose people are known for doubting everything. The challenges faced by Groupe Capitales Médias, whose future remains uncertain, and many other newspapers and media outlets demonstrate the importance of the FPJQ. More than ever, it must channel the energy and indignation of the torchbearers of the fourth power. Our journalists cannot do their work without the unwavering support of citizens who are convinced of the need for democracy, which, as Winston Churchill put it, “is the worst form of government except for all the others.”

This article appeared in the FPJQ’s journalism magazine Le Trente on November 21, 2019.