Preserving our broadcasting history

The University of Toronto’s Media Commons is building an archive of Canadian broadcasting media materials relating to the audiovisual and media communities, the entertainment industry and popular culture in order to preserve an accurate, fair and comprehensive historical record for us all.

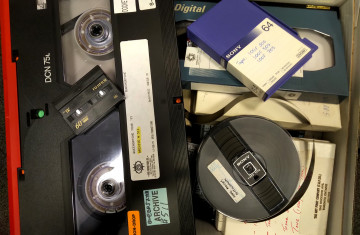

A recent donation to the U of T Media Commons archive reflects the evolving technologies and formats used to record broadcasts over the years.

Broadcasting is one of the most accurate reflections of our evolving history and culture. It’s been used to record and disseminate knowledge of the world’s people, places and events since the 1920s. Radio and television – and now podcasts – are mirror-like reflections of our culture, and most people in Western society receive most of their news, weather and sports, entertainment, cultural cues, business trends, humour, fashion, and even ideas as to what is cool and politically correct from these broadcasts.

Phil Graham of the Washington Post wrote that “newspapers are the first draft of history.” While that may have been the case up to the 1970s, since then the first draft of history has been provided by broadcasts. They are more than just actuality, though. They can also be drama, stories and re-enactments. In many cases a fictional broadcast gives greater insight into society’s concerns and fears and joys than a documentary does. And it would appear that most people increasingly enjoy the experience of listening to or viewing a broadcast document more than reading the written word.

There are certain qualities to sound and moving image documents that go well beyond the printed page in helping us understand the world around us. For example, sound recordings reveal content and aural information. They are not just a description of what something or someone sounds like, they are the authentic voice, the actual performance. They are the difference between reading about a piece of music vs. actually hearing it, between reading someone’s memoirs and listening to them reminisce. What is heard is far richer than what is read, and can almost place the listener in the same room as the performance or speech.

Sound and moving image documents go well beyond the printed page in helping us understand the world around us.

Likewise moving images reveal both visual and aural information over time. They are not a description of what something or someone looks and sounds like – they show what they look and sound like, and they show change, movement, processes, things happening, progressing. They have many more layers than a written account, and they easily and smoothly engage the mind and senses on many levels. They are the closest we can come to seeing with other people’s eyes and hearing with other people’s ears.

Broadcasting documents have been undervalued for many years, probably because of two things: most are created for commercial purposes and therefore are somehow thought to be incapable of being intelligent or truthful; and a large percentage of broadcasting documents are considered to be “popular culture” – appealing to the lowest common denominator – and thus do not reflect the best of society. There can be no doubt that broadcasts can be shallow, misleading and have little redeeming value, but so can every other type of document created for commercial reasons, regardless of format. And aside from the argument that broadcast documents can just as well be “high culture,” it is productions aimed at all parts of society that need to be considered if we want an accurate, fair and comprehensive historical record. For all these reasons and more, it is to Canada’s advantage to try and preserve a wide range of broadcasting documents.

The University of Toronto’s Media Commons is dedicated to acquiring and preserving archival and special collection material of Canadian and international significance relating to the audio-visual and media communities, the entertainment industry and popular culture. Its mandate is to support the curriculum of and research in the various disciplines taught at the University of Toronto with media-based materials. We serve the university community, but we welcome the general public as well.

We want to document all aspects of broadcast production – as a creative activity, as a business, and as a record of evolving techniques and technology.

We seek to collect all the material relating to broadcast productions both analogue and digital: the finished masters, of course, but also the raw material such as b-roll, full interviews, the various rough to fine cuts, soundtrack elements and materials used in websites. Just as important are the associated textual documents – proposals, treatments, budgets, company policies, memos/correspondence, contracts/agreements, cast/crew lists, call sheets, research files, production files, promotion and marketing materials, press releases and reviews/critiques. We want to document all aspects of broadcast production – as a creative activity, as a business, and as a record of evolving techniques and technology.

The names of all the collections acquired thus far are too numerous to include in an article of this length. Suffice to say they are broad and varied. For example: from the ranks of media executives, we have the Moses Znaimer (Much Music, Zoomer Media) and Jay Switzer (CHUM/CITY) archives; from the world of broadcast journalism we have collections from Patrick Watson (This Hour Has Seven Days, Witness to Yesterday, Titans), Michael Maclear (The Ten Thousand Day War, Maclear, Beautiful Dreamers, Flight Plan) and Peter Mansbridge (The National); from the radio community we have Orbyt Media (Command Performance, Private Session), Doug Thompson (The Producers, Music Express Radio Show), as well as the huge treasure trove of 1930s-1960s British, American and Canadian transcription discs from Trent Radio. From the world of television producers we have the archives of Shaftesbury (Murdoch Mysteries, The Listener, Life with Derek), Linda Schuyler/Epitome Pictures Inc. (the various Degrassis, Liberty Street, Riverdale), Big Coat Media (Love it or List It, Animal Magnetism), and Insight Productions Ltd. (Juno Awards, Canadian Idol, Open Mike, Heart of Gold, etc.). From the beginnings of broadcast comedy is the Johnny Wayne Collection (Wayne & Shuster), and from the community of advertising production we have materials from Fritz Spiess, Syd Kessler & Jody Colero, and Norm O’Dell. Finally we have the full archives of the first 75 Heritage Minutes, donated by Historica Canada.

The production of broadcast documents continues apace, and thus the acquisition and preservation of those documents must also continue. This is a costly and labour-intensive activity, however, and it has become apparent that the full costs can no longer realistically be borne by the collecting institutions. We hope that members of the broadcast community – both companies and individuals – and those who believe that the history of broadcasting is worth keeping will consider supporting the institutions in whatever way they can.